Is your child excessively self-critical, afraid of doing a task ‘wrong’ or prone to taking a while to bounce back from disappointment? They could be struggling with perfectionism.

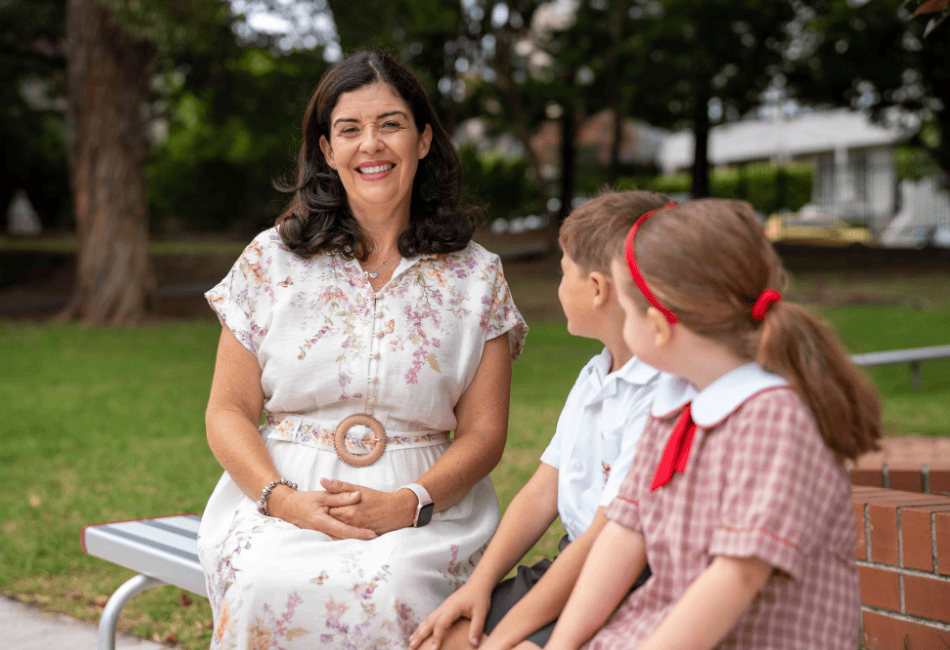

Jan Robinson speaks regularly to students and teachers about the difference between ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ perfectionism, as part of her role within Sydney Catholic Schools’ Research and Innovation team.

She said the myth of the “perfect life” is pervasive, and “perception can be as hampering as reality” if it has as much bearing on your behaviour – or your child’s.

“There is a perceived need to always be reaching for more” – Jan Robinson

“Often we feel some responsibility to be publicly showcasing how healthy, fit, beautiful, clever, or skilled we are. But perfectionism is not always negative,” Mrs Robinson said.

“It’s a multi-faceted trait that varies from the healthy to the unhealthy.

“Understanding where behaviours fall on that spectrum can determine whether it is supporting a child’s learning, or creating barriers to it.”

SIGNS OF HEALTHY VS. UNHEALTHY PERFECTIONISM

A healthy dose of perfectionism can help us learn and achieve, but too much can lead to pressure and procrastination.

‘Healthy’ perfectionism is when students:

- Strive for excellence and are satisfied with their personal best

- See success as a mix of effort and ability

- Allow for limitations and imperfections

- Accept failures and keep perspective when they are frustrated by failure

‘Unhealthy’ perfectionism is when students:

- Have excessively high standards for themselves and others

- Focus too much on mistakes

- Avoid taking risks

- Show self doubt, poor organisational skills, and procrastinate

- Believe their parents expect too much, and may expect parents’ criticism

- Think their self worth is equal to their grades

PARENTS: FIVE WAYS TO DEAL WITH PERFECTIONISM

Here are some ways you can support your child if perfectionism is starting to affect their learning and life.

Here are some ways you can support your child if perfectionism is starting to affect their learning and life.

- Examine your own behaviour

Mrs Robinson said parents’ behaviour can unintentionally promote or support perfectionistic behaviour.

“The message a parent believes they are giving is sometimes seen or heard as something quite different by their child,” she said.

“If parents never show flaws, struggles or even failures, they are modelling perceived perfection”

“If parents put focus on achievement rather than the ‘learning’ that has happened, it may suggest that grades equal worth.

“Sometimes a parent’s encouragement to work hard is interpreted as a desire for perfection.

“The feelings it can evoke in a student? Double failure. They failed to be best, and failed someone they love.”

One way to avoid this is to acknowledge stress and show your child how you overcome it in a positive way.

Consider how to model acceptance of shortcomings or mistakes – your own, or those of others.

Laugh at yourself, share your faults.

Try not to do everything for your child, as a perfectionist may interpret this as implying they can’t do it well enough themselves.

- Provide emotional support

Acknowledge and respect your child’s feelings, both positive and negative.

Give unconditional love that is unrelated to behaviours, successes or failures, and show love for who they are as a person.

Encourage the understanding that working through conflict in friendships is normal and may be part of developing deeper bonds, rather than a reason to abandon a friendship.

Teach them to keep frustrations and mistakes in perspective.

- Communicate openly and honestly with your child

Give praise when needed and deserved, and reprimand for major issues only. The rest of the time, discuss and negotiate ways to improve or move forward.

Encourage your child to admit to problems or personal difficulties and see them as a part of life that can be responded to, rather than fretted about.

Be aware of giving unspoken or implied criticism, such as using a disapproving tone of voice, a frown, a raised eyebrow.

Remind your child from an early age that there is no such thing as ‘perfect’, and that it is more important to try their best.

- Encourage realistic goals

Setting goals that are possible to achieve but still carry a hint of challenge is the ideal.

Setting goals that are possible to achieve but still carry a hint of challenge is the ideal.

A child’s confidence benefits from the boost achieving a goal can give.

“Practice setting goals that have small, incremental increases in their level of challenge may support greater willingness to undertake challenges by reducing a fear of failure,” Mrs Robinson said.

- Provide opportunities to build resilience

Encourage your child to be an ‘explorer’ of life. Give them safe but broad parameters to try new things – whether a food, hobby, skill or experiencing a new place – and let them go.

They’ll discover that trial and error is a valid way to learn new things, and that a mistake can teach more than immediately finding the right way can.

It also empowers them as they experience a time when they have control over their life.

PERFECTIONISM IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

“An article published in early 2021 addressed the importance of students today developing ‘tolerance of uncertainty’, which is very relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Mrs Robinson said.

“It stresses the great value that ‘the ability to act despite unknowns, complexities or incongruences’ can have for students in learning and in life.”

Another help is to give students the opportunity to see that, in some situations or tasks, there is more than a single way to achieve success.

“Learning that there can be multiple correct alternatives can be very liberating,” Mrs Robinson said.

By: JADE RAMIREZ